[ad_1]

Have you spotted the Killmonger dreads? They’re everywhere these days. What started in Marvel’s Black Panther film is now ubiquitous in gaming. And these dreads are not just on the heads of Miles Morales or Tekken’s Eddy Gordo. They’re in character creators too. The style began as fashion but has quickly become a stereotype.

Black players have noticed. “In general, we get stuck a lot of the time with the afro, the smaller afro, the buzz cut, or the gel braids going back, or nasty dreads that are symmetrical on either side. Or they all love the Killmonger dreads now,” Twitch Ambassador and content creator Danielle Udogaranya (aka Ebonix) told me recently, all but ticking the same old options off on her fingers.

The Killmonger dreads are a striking example of how representation in these kinds of expressive tools urgently needs to move away from stereotypes. Character creators are a fascinating part of video game design where players decide how they look on screen, with opportunities for positive representation as well as negative reinforcement. When developers get this stuff right, players can see themselves in a video game and feel fully immersed. But when representation is poor or lacking, it can be a disaster.

I was curious to find out more about the process of developing character creators, to understand the challenges developers have to overcome and how representation in video games can be improved. And so, over the last few months I’ve spoken to some of the people behind Baldur’s Gate 3, Diablo 4, Cyberpunk 2077 and more to understand the key decisions and priorities in play when creating such a tool.

From a single hairstyle grew broader questions about character creators: Why are they so hard to get right? What are the forces that shape their development, and how are these forces changing? And what might the ultimate character creator look like?

Character creator pitfalls

Adding a character creator to a game comes with huge risk. Get it wrong and at best your game becomes a meme; at worst it can alienate a community. Take Mass Effect: Andromeda as an example.

“My FemRyder looks really good but there is no way to make a similarly looking BroRyder that doesn’t look like mashed potatoes,” laments one Reddit user playing Andromeda, among plenty of similar posts after a quick Google. I had similar issues with Andromeda and other games: perhaps there aren’t enough beard options, or faces don’t compare to in-game NPCs. Or maybe everyone just ends up looking bizarre.

For its first few weeks after release, Andromeda was less a space-faring RPG and really just a series of GIFs on social media sites. That’s bad news for the game, certainly. But in some cases, and for many players, particularly those from minority backgrounds, character creators and their limits in terms of representation pose a far more serious problem.

Examples of this are not hard to find either. Too often Black skin tones and authentic hairstyles are presented as a handful of extras outside of default whiteness. It took World of Warcraft 15 years to add ethnically diverse player characters to the game. Sims players took to change.org to request more variation in darker skin tones. LGBT+ representation is often lacking too, as developers fail to include sufficient pronoun options or tie gender expression to binary choices.

That was the case in Cyberpunk 2077. CD Projekt Red’s game was praised for the detail in its character creator, but also criticised at launch for its poor trans representation. This mostly related to the lack of representation and consequence in the game world itself, as Stacey Henley wrote for PC Gamer. But it also comes back to a character creator in which players can freely choose any genitalia, while pronouns remain tied to binary voices. Not only is it impossible to be non-binary, a character’s trans identity relates solely to their genitalia.

These are memorable examples of games getting it wrong, but they serve to highlight the risks involved in adding a character creator in the first place. So how do you get it right?

From paper to screens

It starts by understanding why games might include a character creator in the first place. Character creation dates back to the original D&D role-playing tabletop game in which players start by completing a character sheet before their quest begins. The first character creators, then, were made from paper and pencils.

“In a D&D game, having custom character creation is actually more important than having origin characters because it’s the original game in which the player is the hero of the story,” says Lawrence Schick, principal narrative designer at Larian Studios and original D&D designer. “In D&D, you are your character, and the majority of players prefer to make their own and then interact with the origin characters as members of their adventuring party. In that context, a custom character creator is essential.”

Character creators can allow players to explore different identities too. As Kylan Coats, founder and lead developer at indie studio Crispy Creative, puts it: “I’m definitely all about empathy, I want to see: what is that experience? How can I relate to it even an infinitesimal amount more? That allows me greater empathy with humanity overall.”

Through my research, it became clear that, fundamentally, character creators act as a two-way mirror. They’re a diverse toolset that allows players to feel seen, but they’re a reflection on developers too. Dig deeper and you can identify the political ideologies and technical limitations the team has worked within.

So let’s try to understand some of these limiting factors.

Setting limitations

“It’s essential that the creator fits the game you’re making,” Street Fighter 6 director Takayuki Nakayama tells me. “More freedom is always fun, but since we’re making a fighting game, we had to balance freedom with the aspect of how things like the length of the character’s limbs would affect the battle experience. We wanted to avoid the need to introduce unnecessarily complex rules to handle this.”

As Nakayama outlines, a development team may want to create a detailed, highly diverse character creator, but created characters will still need to fit in the game world and within gameplay parameters, no matter the genre. Sometimes, choices have a knock-on effect on other areas – for better or worse.

“It’s essential that the creator fits the game you’re making.”

Take Cyberpunk 2077, for example. The aim for the game was full immersion, with the use of first-person perspective to put players into the body and mind of protagonist V. An impressively detailed character creator at the start allows players to create their own interpretation of V – right down to eyelash colour.

“We are always about creating immersive, story-driven RPGs and even if it’s in first-person perspective, we wanted you to feel like the character you want to be,” says CD Projekt Red lead character artist Grzegorz Magiera, who notes you still see V’s hands and sometimes the full character in certain situations.

Yet there are still limitations to the creation tool. Where many character creators allow players to experiment with body size and height, Cyberpunk 2077 has just two static body types (broadly, male and female presenting). This decision was made to prioritise a different form of customisation: the garment system.

Fashion is key for players to express themselves as V throughout Cyberpunk 2077’s world. The game contains thousands of items of clothing and the player is able to dress V in layers, so the body types are restricted to ensure this garment system works as intended.

It’s a trade-off and in turn, every other element of the creator became hyper-detailed to offer a high degree of expression. “You can mix it the way you want it, the way you feel it’s best for you,” says Magiera. “Everything together gives you the full variation of possibilities, and this was our goal.”

As an immersive, voiced RPG, Cyberpunk 2077 has thousands of lines of dialogue. As such, the character creator ties pronouns to vocal choice with only two options. Magiera explains to me this was purely a technical decision as the dialogue would require too much translation and voicework for the team to accommodate more than binary pronouns. As for the inclusion of genitalia, this was simply another detail to help players embody V, despite rarely being visible.

The character creator in Cyberpunk 2077 is deeply shaped by the priorities of the developer, then. And it’s by no means alone. Diablo 4 is another blockbuster RPG that similarly does not allow players to alter body shape. Here, though, as a fast-paced action game, it came down to accessibility. “We’re building a game where PvP exists, so we need to ensure that players can identify what class they’re playing against very easily,” explains accessibility design lead Drew McCrory. Fixing classes to body shapes allows for the creation of strong silhouettes, in other words. “Being able to very cleanly identify everybody, even if it’s murky, is super critical,” says McCrory. “That also dovetails into the player fantasy of the classes, it all is very symbiotic.”

Many of the blockbuster developers I spoke to had similar stories: the teams placed limitations on the character creators because of other elements of the game they were trying to support. But what if your main limitation is actually money? Indie games frequently work within tighter budgets in ways that impact game design. Perhaps the game will be in 2D rather than 3D, or won’t be voiced. In turn, these decisions shape the character creator too.

“As an indie, you have to really pick your battles and pick what you’re going to spend your time and your money on,” Coats tells me, discussing the RPG A Long Journey To An Uncertain End. “You also have to stand out in the space.”

Picking your battles sounds good. But even simplifying things can be complex in video games. The use of 2D art, for instance, might seem easier to manage than 3D models and animations, but it can still bring its own issues. Due to its 2D art, the character creator in indie game Arcade Spirits: The New Challengers does not feature sliders, instead offering preset options. Yet these are entirely hand drawn, and every permutation adds to both representation and workload. “You have to draw a line somewhere,” says creator Stefan Gagne, “and say: this is how much we can realistically support.”

However, as I learn, budgetary limitations don’t have to hinder innovation when it comes to diversity and representation. In fact, it can be the opposite.

Ensuring diversity

Regardless of the choices and limitations, diversity in character creators is a central concern for every developer I’ve spoken to. Erin Ellis, localisation programme manager at Amazon Games for Lost Ark, grounds it all in personal experience. “Just as there is a place for all sorts of people in the real world, it is important that our fantasy worlds, our idealised play worlds, have a place for everyone as well,” she tells me. “I grew up as a big nerd who wanted to get into nerdy things like games. However, I was always a little hesitant since I rarely saw characters who looked like me in that media; it felt like maybe the space was not open to people like me.”

She continues: “Even looking from a strictly mercenary business lens, why leave so much of the potential world market on the table when it is relatively minor effort to add in more customisation compared to all that is being created to build a living, breathing world?”

So why is it that in some areas indie developers are leading the charge on diversity? Coats, like Ellis, believes it helps broaden the audience of an indie game. “There’s not a tonne of data on it,” he tells me, “but from the data we do have: queer gamers, when they feel represented, not only do they spend more money on the games that they purchase, but they talk about them more.

“Word of mouth is still the most effective marketing. So by doing just a few fairly minor things, you can make a vocal portion of your community feel seen and want to talk about your game. Why wouldn’t you do that?”

Moreover, small indie teams can be agile. “We don’t have to go through approvals,” Coats continues. “We don’t have to get legal to sign off on something. Back when I was in AAA, it felt like you always had to get permission from someone. And that person was generally a straight, cisgender, white male, and they’d be terrified of anything coming up.”

It’s also difficult to branch out of the perceived default of straight white cisgendered male characters. “Inclusivity has gotten much better in the past few years, but when I was working in AAA, there was a sort of soft discrimination of you wouldn’t get an outright ‘no’ if you wanted to include a queer character or trans character or character of colour, but you did have to justify their inclusion all the time,” says Coats. “Whereas if it was a straight cisgendered, white, male character, it was like ‘oh yeah, just put that in’. But if you want to just mix it up, it’s like ‘whoa, why are we doing that? What’s the reason behind it?’. Because they exist, because these people are here, we don’t have to give them some tragic backstory to exist. They can just be.”

“These people are here, we don’t have to give them some tragic backstory to exist. They can just be.”

He concludes: “I think there’s a responsibility for indies to keep exploring this stuff. Otherwise, if you wait around for projects with hundreds of millions of dollars of budgets, it’s going to take them a while to get there.”

Gagne feels similarly, and tells me representation requires both a passion for diversity and the money to see that vision through. “So you get studios which have one but not the other,” he says. “AAAs which have ridiculous amounts of money but they’re just not really interested in putting it into this area, or indies which would love to give you everything under the sun in terms of representative character creators, but they’ve got practical limits, there’s only so much you can do.”

Diversity is therefore at the heart of both games – and their character creators. For A Long Journey…, Coats and his team created a diversity matrix to flip norms on their head, ensuring all NPCs in the game represent a spectrum of non-white, non-male, non-heterosexual, non-cisgendered people. “From the start of the game, we wanted that inclusivity, that accessibility, and that [philosophy] bled into our character creator,” he tells me.

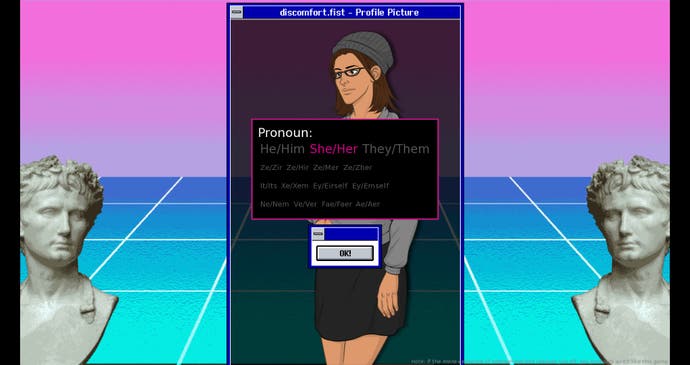

And it pays off. One striking area of innovation in both these games is the range of pronoun options, allowing players to identify not only with he/him or she/her pronouns, but they/them and neo-pronouns.

This kind of option is rarely included in high-budget games, though there are some exceptions. Street Fighter 6 allows players to choose pronouns, between male, female, and human, so characters in the World Tour mode can address the player accordingly. “Representation of diverse gender identities is important,” Nakayama tells me, “both to me personally and to the company, so it felt essential to reflect this in the game.”

Then there’s Baldur’s Gate 3, which separates body type, identity, and voice, allowing players to fully explore their character’s gender identity. “We make games that are about being who the player wants to be, not who we want them to be,” says Schick. “There is no functional value to limiting identity combinations, and in a player base of millions, every possible combination will be desired by somebody. Once again, the goal is: no limits.”

In Arcade Spirits: The New Challengers, a variety of non-binary options are included, such as Ze/Zir, Ze/Hir, and Fae/Faer – and that’s on top of free-typing a chosen name. Of course, with this being a text-based game without voiceover, the team could experiment with pronoun options.

“You notice in Mass Effect, you’re always ‘Shepard’ even though technically you have a first name,” says Gagne. “But the game can’t pronounce it because it’s literally just anything you want to type in there. There are limitations when you’re fully voicing a game. But even within those limitations, you can go the extra mile and do variations of lines for different pronouns, even for a wider range than the standard three. It’s really just a matter of budget and legwork you want to do in order to make sure you’ve got representation for your community.”

More specifically, Brittain Avery is credited for Pronoun Research and was responsible for researching and creating a lookup table for the correct pronoun and conjugation. “Implementing it was really easy,” said Gagne. “I like to say it took the cost of a single soda and a bag of chips I consumed while I was getting it up and running in about 20 minutes.”

| Image credit: Fiction Factory Games

In A Long Journey…, Coats included a custom pronoun editor where players can freely type preferred pronouns. Again, the text-based limitation allowed for this innovation. “How can we be inclusive to people who use neo-pronouns without having this big long drop down list of everything?” asks Coats. “These are just variables. We’re just making a video game, it’s ones and zeros. You can customise your name. We have player input for text. Pronouns are just text, let’s just include a custom pronoun editor. I don’t want to say it was trivial, but it was a lot easier than every AAA studio that I was at made it out to be.”

“I don’t want to say it was trivial, but it was a lot easier than every AAA studio that I was at made it out to be.”

Making this custom pronoun editor a success was a “pretty big motivator for the team”, Coats tells me. “We approached it like, we’re making a tiny little indie game, but we are contributing to the overall gaming space by doing something that’s new.” And the end result is that there will be a commercially released game that has a custom pronoun editor. “Other people can point to that and look to that, and take that as an example with them if they’re doing other indie games or AAA. This is how they did it, we can do it too.”

There are a number of areas where developers are fighting back against the idea some things are too difficult to implement. All the developers I interviewed were passionate about including authentic Black characteristics. To do this they consulted with internal groups, localisation, and culture teams to determine what should be included – and the results here are more positive than the norm.

One outstanding example, however, is Lost Ark. The Amazon-published MMORPG was originally developed by Korean studio Smilegate RPG and was already hugely successful. Yet when Amazon localised the game for the West, there was an opportunity to improve the Black representation in the character creator specifically, by adding a broader range of skin tones and more varied, realistic hairstyles.

Localisation programme manager Erin Ellis isn’t a modeller, but explains that curly hair is more difficult – and therefore expensive – to model than straight hair due to transparencies and layering. Further, darker skin is easier to realistically light due to light refraction through paler skin, even if this level of graphical fidelity isn’t required in the vast majority of games.

“To me, the argument that curly hairstyles or dark skin are ‘too hard’ seems like an excuse to not push the medium or the tech forward,” says Ellis.

Traditionally, the scope of character designs and customisation options are considered during the design phase of a game, so that any technical or budget constraints can be accounted for. Amazon didn’t have that luxury with Lost Ark. Instead, the team collaborated with Smilegate RPG with new suggestions. “We came into the conversation in a collaborative manner, suggesting a number of different textured hairstyles as inspiration and left it to the developers to determine what specifics would work best in their engine,” says Ellis. “And we got some great options for all characters, not just brown ones.”

Despite these success stories, there’s one area of representation that all-too-often is lacking entirely: disability. Forza Horizon 5 is perhaps the most well-known example of a game that allows players with certain disabilities to feel seen, due to its prosthetic limbs and, in a later update, customisable hearing aids. Yet these can be included more easily as they don’t drastically alter the body shape of the character model, nor do they change the game experience. These are purely cosmetic options for representation.

Gagne explains to me why true disability representation is so difficult to achieve. “The issue with disability representation is that in order to do it for mobility impairments or different body shapes, you may need a different animation rig,” he says. “You need to be able to have a character who can be in a wheelchair, or a character that’s on crutches, or walks with a cane. You need to be able to account for a character that’s missing a limb. These are not things that are easy to do, because you kinda have to design your whole game around being able to support that character with those abilities in any situation.

“It’s absolutely a challenge, I’m not going to deny that. But I think that is the next level that a developer can reach because it’s a challenge.”

“I would love to see a AAA that actually puts the focus on this and provides the ability to have an equivalent situation and an equivalent experience regardless of the character’s abilities. It’s absolutely a challenge, I’m not going to deny that. But I think that is the next level that a developer can reach because it’s a challenge.”

Restricting player expression

Speaking to these developers, it became clear: character creators for most games are shaped by their limitations as much as their features. It’s not just about how many hairstyles there are to choose from – it’s about the way one developer wants to foreground its garment system, while another wants to maintain recognisable silhouettes.

Often, leaving stuff out is as important as putting things in, so restricting players’ options becomes an artistic choice. In the words of Magiera, “We try to support many perspectives, but not too much, because then you will be overwhelmed. Quality is more important”.

What’s imperative is maintaining a feeling of authenticity both for the player and for the game world.

As an example, look at Street Fighter 6. Nakayama tells me: “We started out wanting to include as many options as possible… but at a certain point we kept the number to the amount where it doesn’t feel like it becomes too difficult to choose a style.”

It’s an intriguing choice, as the finished game does allow for some extremely creative visions, resulting in characters that sometimes barely look human. Artistically, though, that still fits within the world of the game and its “street art” foundation. “What counts as a ‘wild’ character varies a lot depending on the player,” says Nakayama. “But giving players a high degree of freedom was always our priority.” Luckily, as he admits himself, Street Fighter’s world is one where stylistic diversity complements rather than clashes with the game’s aesthetic.

The same is true for wrestling, of course. “It’s interesting because we’re sports, but we’re also sports entertainment,” senior game designer at Visual Concepts David Friedland tells me. He explains that while certain simulation elements must be present, the only limitation on character customisation is working within the combat system.”I grew up loving the early days of WWE, where they had these crazy characters, people would come out with all sorts of wacky gimmicks,” he says. “And we want to allow people to do that.”

-(1).png?width=690&quality=75&format=jpg&auto=webp)

The WWE2K series gives its players a lot of freedom, in other words, as part of its “fantasy fulfilment” – even allowing them to import custom images. The flipside, however, is moderation; Friedland explains there’s a process to review all uploaded content that involves both a moderation team and player feedback, with repeat offenders banned.

Other developers are stricter with what they allow players to achieve, focusing more on artistic integrity. With Arcade Spirits, Gagne explains that the same artist created the character creator parts and the game’s NPCs in order to ensure cohesion of style with a consistently colourful palette. “You don’t want to put in elements that just don’t seem to mesh with the aesthetics of the rest of the game,” he says.

Similarly, Diablo 4 has a particular artistic vision that defines both the world and the character creator. “Sanctuary definitely has a style,” says McCrory. “It’s a very dark, foreboding place and that level of realism within the fantasy context, I think, is really critical to hold on to and make that feel carry through to character creation.”

What’s the future of character creation?

After speaking with these developers, it was clear to me that character creators are improving, but there is still work to be done on both a technical and representational level.

Developers continue to innovate, though. Visual Concepts is willing to let players upload pictures of their own faces for their wrestling characters and while the results currently aren’t perfect, it’s a step towards ultimate realism – even as just a starting point. Along with that comes a focus on the community, with Friedland telling me there are plans to allow players to share the characters they make across platforms.

-(1).png?width=690&quality=75&format=jpg&auto=webp)

Again, as Street Fighter 6’s Nakayama points out, moderation is key. “In terms of the future, allowing players to play online together brings with it the need to prevent people from being hurt by others’ creations, so options such as hiding custom characters or replacing them with defaults would be a good way forward,” he tells me.

Beyond innovative technology, though, the real future of character creation is one of diversity and representation. It’s not about simply adding more options, but making sure those options are authentic.

“I feel the ultimate character creator would have sliders and colour pickers to be able to make just about any human shape,” says Ellis. “I’m talking the ability to be tall, short, buff, skinny, or curvy, all regardless of character sex or gender. I’m talking the option to freely add stamps for scars, freckles, skin conditions over the body. I’m talking the ability to have varying numbers of digits or limbs, or wear assistive devices like glasses or hearing aids if not leg braces or wheelchairs. I’m talking the ability to have basically any sort of hairstyle possible in reality, to match all the cartoony ones gamers have begun taking for granted. Especially as processors and game engines become more powerful, we should be able to expand those options as a default, even in games that need heavy optimisation.”

“The future needs to be that broader representation is a given, not a nice-to-have.”

She also has a more philosophical take on diversity. “The future needs to be that broader representation is a given, not a nice-to-have,” she tells me. “When it comes down to it, the more available options in a character creator and the more different-looking characters that appear in a game world, the more people who can see themselves in that world and want to engage with it. That means more people playing and enjoying games, which is something that everyone in the industry should be striving for.”

And when a character creator still doesn’t meet the standards of its audience? This is where modders step in.

The Sims 4 content creator and Twitch ambassador Danielle Udogaranya (aka Ebonix), who pointed out the Killmonger dreads to me, is celebrated in the game’s community for her authentic Black hairstyles and outfits, which are publicly available for all to use.

“I started making custom content because there was a lack of representation,” she tells me. “I started with the dashiki [a colourful African garment] because I wanted to tell stories that I felt connected to and relate to through my Sims. And I wasn’t able to do that due to the lack of assets available.” Creating her own character assets is a form of “taking back control as to how we should be seen in games” and battling stereotypes – those Killmonger dreads, for instance.

.png?width=690&quality=75&format=jpg&auto=webp)

.png?width=690&quality=75&format=jpg&auto=webp)

What’s more remarkable is that Udogaranya is completely self-taught in the Blender software she uses. She’s been able to achieve much of what some developers haven’t been able to through “perseverance and spite,” she tells me. While she’s watched countless tutorial videos, she describes her knowledge as “a bit of a quilt.” And there are benefits to this approach. “I feel like it’s been helpful in a way because I don’t feel limited in terms of what I’ve learned,” she says.

She suggests game designers need to really study the intricacies of non-white cultures. “I think the more passionate you are about having inclusive hairstyles and options for all of the players, the more you’re going to want to actually get into those intricate details,” she explains.

The reaction to her work has been “a massive outpour of love and support.” It’s also transcended the games industry and moved into the realm of pure art. Recently, her Sims work was exhibited in a gallery in Italy. “How we are seen in games is an art form, it’s not a technicality,” she says. “You have to look at it from a different perspective and not just ‘we have to include you because we want to make sure we’re doing our duty’.”

She continues: “There are so many little things I put in that Black players pick up on because those are the small things that matter to us but I know wouldn’t matter if you’re not from that community. There’s a real appreciation for the time and effort and attention to detail that goes into the hair I make.”

“How we are seen in games is an art form, it’s not a technicality.”

That, really, is the power of truly authentic representation: sometimes the smallest details can make a big difference and make a community feel seen. There is value in precision and study and careful thought. It certainly beats repeating the same old hairstyles.

So what might the ultimate character creator look like? I see now it’s one that serves player and game alike. It provides authentic, diverse options, but it also allows people to represent themselves within the context of the game. It’s simple enough to provide near-endless authentic options as a standalone tool, but the results must serve the narrative. As these developers have shown, there are multiple methods to achieve this, with further room for improvement as technology – and the industry – evolves.

Creating a wealth of options isn’t necessarily difficult, then. Allowing players to authentically be part of a game world is the real challenge.

[ad_2]

Source link