If there’s a sense of burning injustice at Rocksteady Studios, it’s probably understandable. Suicide Squad: Kill the Justice League is filled with little moments of brilliance: humour, style, expression, that signature rhythmic, flow-state approach to combat. There’s no question – as there rarely is with any video game – that its team was remarkably dedicated to making it as good as it could be. It’s just that for each upshot there’s a matching, crashing downturn, and in looking for a cause it’s difficult to see beyond the ambitions that this game has been asked to juggle.

All at once, Suicide Squad: Kill the Justice League must be a live service game that pays for its extraordinary, almost nine-year run-up time after 2015’s Batman: Arkham Knight, plus the support of those live services beyond launch. It must feature multiple main characters that not one, but two distinct Hollywood films – plus Birds of Prey – have failed to generate any kind of public good will towards (or even mild interest in). And it must deliver, or at least seem to deliver, on its promise of making antagonists out of and subsequently killing the Justice League – a group of beloved, decades-old icons that have in part earned their iconic status from not dying. (And which come with a subsection of fans – emphasis on the subsection – known to be as toxic as they are dedicated). All together, it means question that arose for most onlookers the moment Suicide Squad: Kill the Justice League was revealed in 2020 remains the same now, and even well into its perpetual grind of an endgame: why?

So, the sense of injustice: with all that to try and pull off, Rocksteady has done a remarkably good job. The problem is a remarkable job in this case equates to a game that wildly oscillates between brilliant and poor, and ultimately lands perfectly square on average. Average, by Rocksteady’s standards, is a disaster. And setting up a studio of that pedigree, that wonderful ability to capture every angle of a character, and that genuine dedication to its craft, to fail in this way is about as close as video games can get to an act of cultural vandalism.

For those who haven’t read the comics and also managed to dodge those Hollywood attempts, the premise of the Suicide Squad is simple. Four mid-tier villains, Deadshot, King Shark, Captain Boomerang and Harley Quinn, are busted out of jail by Commander Waller, head of a shadowy organisation called ARGUS. Waller injects a remote-activated bomb into the back of each of their heads and now this group, officially called Task Force X, have to do whatever they’re told. In this case, that’s defeating a very ominous invasion from supervillain Brainiac, who’s also managed to take over most of the Justice League – the Flash, Green Lantern, Batman, and Superman, but not Wonder Woman – with mind control.

Cue a lot of neon spray paint, subversive wisecracking and inter-villain banter. But despite having come fully prepared for a playable XD emoticon, Suicide Squad is genuinely quite funny – in many ways it’s an action-comedy, carried less by its overt story than the little under-the-breath quips and what you might call industry-leading combat barks. The squad themselves quickly move from annoying oddballs to lovable oddballs (something referenced in fourth wall-breaking fashion by King Shark part way through, as almost all story developments are here). Shark is a little close to the comedic literalism of Drax, but makes up for it with some strong pun game and a few smart put-downs. Boomerang never gets beyond comic relief but rarely has to, with a million jokes thrown at the wall and just enough of them sticking. Harley Quinn is Harley Quinn, inscrutable, impulsive and slightly sad. And Deadshot, while being a little too close to a talking character sheet at times – motivated by: revenge; scared of: tight spaces – still works well as the straight-man foil to the rest.

All of this is complemented by typical Rocksteady attention to written detail, particularly in the deeper parts of menus and side activities. Little touches like codex entries are an artform, and treated as such by this studio – there’s a reason Wonder Woman’s, written in the cynically philosophical voice of Lex Luthor, went viral over the weekend – while much of the supporting cast are excellent as well. Luthor in particular is brilliant whenever on screen, perpetually exhausted – he’s a little over it – but also never without an ulterior motive, or that tiny glint of resentful arrogance, like it should’ve been his apocalypse everyone had to come together for, not this overrated Brainiac’s. The perfect way to write an evil genius.

Waller, by contrast, is incredibly one-note, furiously wailing from beginning to end – this is lampshaded by the squad’s own little quips, but doesn’t make it any less ridiculous. We could’ve at least started with a bit of simmering rage, rather than going straight to perpetual boiling point.

More disappointingly, the same issue goes for the Justice League themselves. It may be a symptom of trying to villainise a group of especially super superheroes, but all of them fall back to varying synonyms for one another, each of them really just plain arrogant. This isn’t helped by the mind control conceit, which almost by definition makes each of their personalities uniformly “bad”, but it’s deeply frustrating: the Flash is cocky, the Green Lantern is smug, Batman is superior. Wonder Woman is condescending, albeit in more of an enjoyably funny way, particularly when paired with Quinn’s adulation, but that’s undermined by the way it just repeats the same personality of the rest of the League. Superman meanwhile is barely anything, his personality subbed out in favour of a metaphor for weapons of mass destruction. He’s just Kal.

Each of your encounters with the enemy heroes will come down to a singular boss fight, with each remarkably similar as well. You’ll go to a location in the city which is conveniently arena-shaped and fight either a giant version of the hero or a human-sized but very, very fast one, each of them either darting around throwing whirlwinds and lasers at you, or loitering up above while conjuring objects and… shooting more lasers at you.

The biggest disappointment of all, given Rocksteady’s brilliant history with him, is the use of Batman. Much has been made of this being legendary voice actor Kevin Conroy’s final performance as the character, but there are no issues at all with the sendoff here. Batman, unlike the other villains, is regularly used as an over-the-radio narrator while you fly about the city, monologuing away to himself under Brainiac’s influence as a kind of extended joke about his own self-importance. It’s a great twist on what’s always been a very self-important character (you can see why Quinn can’t take him seriously, and Batman has, whisper it, always been kind of funny anyway). And Conroy is wonderfully game, clearly relishing the chance to cut loose and go fully arch with the tone after so many years playing it straight, and to be the butt of some excellent jokes when he is. There’s also a heartfelt thank you and tribute to his brilliant work after the credits.

The issue instead is much simpler, which is that the actual playable encounters with Batman aren’t very good. The first is a nice idea: a walking tour through an abandoned, lights-out “Batman experience”, where his history – and that of the previous Arkham games – is retraced alongside some grisly remnants of evil Batman’s work. The issue is the wasted potential: the lights go out, you’re all split up and must find your way to an exit with nothing but a flashlight, it’s all set up for survival horror, but the horror never comes. It’s a few, repeating, largely inconsequential Bat-mines on floors and walls, and little else.

Likewise, the second encounter – the real Batman experience, as Batman himself says – is an even better idea, but isn’t any better in practice. It’s a slow, highly repetitive trudge through pop-up, one-hit-kill enemies and more of those mines, followed by a desperately disappointing bossfight: a giant Batman that stands still in front of a big ledge and shoots lasers from his eyes, the kind you’ll find much more varied, interesting, and challenging versions of in say, Returnal, or even just Ratchet and Clank. The big opportunity here was painfully obvious: have all the tools and toys we’ve seen Batman use over the years in Rocksteady’s own games come out to play. Have him hoist your pals up from behind you after a split second looking in the other direction, or just wing a Batarang at your head. To waste all that rich material, and for it to be wasted by Rocksteady, is an extraordinary shame. There’s not even a moment where one of you goons yells “It’s da bat!”

This is arguably where the real issues with Suicide Squad: Kill the Justice League occur – it’s combat. Or rather, the impact on its combat by the decision to make this game a live service.

Fighting in Suicide Squad begins quite badly. The basic premise is this is a third-person shooter with a heavy emphasis on traversal, but also one with four distinct characters, and some actually quite inventive carry-overs from the hand-to-hand combat of the Arkham games. One of those is a combo system, typically capped at 50, which boosts all kinds of things the higher it goes, and is lost not by taking a hit or whiffing one of your own, but by filling up a combo breaker gauge (which is gradually done by taking a hit or whiffing one of your own).

Towards the latter part of the game, you’ll regularly be sitting at high combo scores and combining other aspects of the system for a type of overwhelmingly chaotic, maximalist, ludicrously fast flow-state combat that feels as much about focusing on the one pertinent bit of information on-screen amongst thousands as it does about actively deciding to do anything. At this point it’s sensational, almost symphonic, with moments I’ve captured purely to convince myself that yes, I really did pull all that off in the space of three-and-a-half seconds.

The reason it begins badly is because there are an extraordinary number of layers to the combat that build up to this point – a necessity for a loot-based live service shooter that wants to give out items with +0.1% buffs and frost damage and cooldown boosts and all the rest. Alongside the combo system is a counter system, for instance, also ported over from Arkham in a way that sits rather bizarrely in a shooter. When one of Suicide Squad’s infinite generic purple enemy not-zombies is lining up an attack, which they do very slowly but en masse, an attention-grabbing counter symbol will appear around them. Switch from holding LT and RT to aim and shoot, to LT and a tap of RB, and you’ll fire a “counter shot” at them, which stuns them or opens them up to certain attacks. This can actually be done before or after they fire, which doesn’t really make sense for a “counter” but try not to think about it too much.

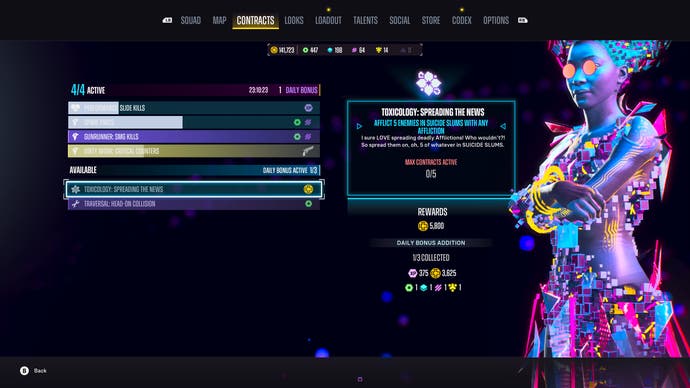

There’s also a curious, contextual melee system – get close to an enemy and tap RT (the shoot button) and you’ll melee them instead. That dovetails with the counter system and a shield system, which can be “harvested” by meleeing enemies you’ve primed first (by shooting them in the legs, hitting them with a grenade, and other specific methods). Then there’s a system of “afflictions”, like frost, frenzy, fire, and so on, that can be attached to enhanced melee attacks and grenades, or via higher-tier weapon bonuses. There are three kinds of ultimate ability: a classic Arkham-style two-button finisher, a multi-target “traversal” move or a late-game “squad ultimate” that impacts your whole team. And there’s the traversal itself, also mapped to, you guessed it, a combination of left and right triggers and bumpers.

This is a lot. And again, in the late game, with sufficient mastery of the initially very counter-intuitive control scheme that severely strains under the weight of all these inputs, this can combine into brilliance. Movement, particularly with Boomerang, who has a range of crackling, elasticated pseudo-teleportation moves, can pair with that to take it up another gear again, a whiplash-inducing spree of self-perpetuating, shield-regenerating, cooldown-resetting magic.

The problem is for most of the main story, and in fact, into the post-game itself, you’re still acquiring new systems on top of the ones you already have. Many players’ experience will be of a 10 to 12-hour narrative that could effectively be a 10 to 12-hour combat tutorial, with each introduction of a new mechanic necessarily delayed in order to let you understand the last. And this manifests itself on-screen, too, with combat actually a deeply reactive experience, responding to prompts to counter, harvest, execute, counter, harvest ad nauseum. It’s only once you punch through this excessively long learning curve that you gain the freedom to take the initiative.

Live service necessities also weigh down on other parts of the game, and while combat gets drastically better with time, these do the opposite, only getting worse. Quest design, for instance, is almost a non-existent discipline in Suicide Squad: Kill the Justice League. The open world of Metropolis (deeply pretty in classic retro-future, art deco style, but totally devoid of people, sense of place, or any real intrinsic reason to explore) is styled like an open play area in Destiny or dare I say it, Anthem, two games that clearly serve as heavy influence for Suicide Squad. In it, you’ll encounter small clusters of randomly spawning enemies, which can be quickly biffed for a bit of pointless loot, or missions that fall under one of roughly a dozen categories.

Within these categories though, each mission is effectively identical. You’ll play through at least one of each by necessity through the story, but then those formats are recycled indefinitely throughout. Like Destiny or Anthem again, there are different categories that they fall into. So, by progressing the story you’ll unlock “support squad” characters, which each have a small list of missions of their own. All of the missions for one character are the exact same format, just taking place on a different cluster of anonymous rooftops in a different part of Metropolis.

As you move into the postgame – where the “real” live service game always begins – it’s time for more repeats, only it’s just slightly bigger, harder jobs you’re repeating, like taking down a giant cannon (never had a clue what these were shooting at by the way, Brainiac already controls the city! There’s nothing to shoot!) or in one desperately boring class of quest: escorting a very slow moving van to its destination.

Repeating missions is one thing – Destiny was infamous for this, having you run through already-completed story quests numerous times, let alone its post-game activities – but Suicide Squad’s issue is that it doesn’t really have missions at all. The main story is a series of post-game activities punctuated by lengthy, lavish cutscenes and occasional boss fights. It’s effectively an entire single-player campaign and post-game constructed of Destiny 2’s Public Events. Go to location, fend off numerous spawns of ever-tougher enemies, complete a rudimentary secondary objective, get loot, repeat.

This, by far, is Suicide Squad’s biggest problem. Its story can be hit-and-miss, its bosses can be misses and its combat can take hours before it hits its brilliant crescendo (and still be quite samey across classes, something Anthem actually did better, but that’s another point). But it is missing the one thing that actually makes service games work. Contrary to what seems to have become popular belief, that isn’t an endless treadmill of earning loot with higher numbers that you use to earn loot with higher numbers. It’s the chance to experience something authored. It’s the power of the raid, the payoff not coming from completing that raid but in the actual opportunity to play it – this is what players grind for! The shifting Vault of Glass, or the eerily gauche, brain-melting puzzle cube of The Leviathan. Even the weekly Nightfalls are the same: linear, structured levels manually designed by human beings. Experiencing these late game activities is a privilege in itself, and Suicide Squad just does not have a single one.

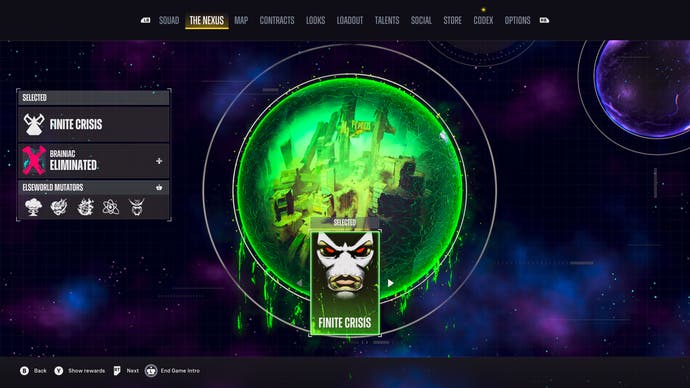

Without it, the entire premise of the game falls apart, despite its undoubtedly snazzy “Finite Crisis” stylings and promises of future roadmaps. The promise there is just of the treadmill getting even faster, as opposed to a chance to briefly hop off and use your freshly-earned rewards to be a part of something cool. Looked at all together, it gets very easy to start falling into facile comparisons between the Suicide Squad and the team at Rocksteady themselves. A team forced into doing something out of character, that starts out an awkward fit but morphs into something oddly but undeniably lovable, only for them to realise there’s no real endgame here. Another low-hanging comparison might be Batman himself. A studio that was once a symbol of something good, somehow turned into the opposite.

Both of those might ultimately be a little trite. There’s no certain cause as to why Rocksteady’s spent such a long time on the type of game so few people want, much as good old-fashioned corporate avarice is the easy and – probably – most likely answer. And there’s certainly no sense that Rocksteady’s team was making this with anything less than total conviction. Whatever the cause, the result is nothing if not a totally fascinating game, one with vast potential and reams of signature Rocksteady detail and panache and all the structure necessary to make a live service shooter that’s genuinely enjoyable for months to come. There’s just no central, underlying game to actually hang it on. A glittering, custom-made suit, without the hero to wear it.

A copy of Suicide Squad: Kill the Justice League was provided for review by Warner Bros.