[ad_1]

If you’ve been to a magic show, or even just walked past one of those blokes who spray paint themselves gold and ‘levitate’ by Covent Garden, you’ll know the feeling. First it’s something between a full-blown “Woah!” and an appreciative “Neat,” then the inner child dies again and it’s back to boring old rationalisation. The deck was probably loaded, the audience member was probably a plant, and that levitating guy is concealing the mother of all wedgies from his hidden harness.

After seeing a couple of different AI demos at GDC last month – and hearing or reading about many more – I realised my reactions to them were pretty similar. There is an initial and very genuine wow, as someone shows you something genuinely new, a weeks- or months-long task performed instantaneously, followed almost immediately by a re-folding of the arms and all kinds of questions – few of which, at least so far, get truly satisfying answers.

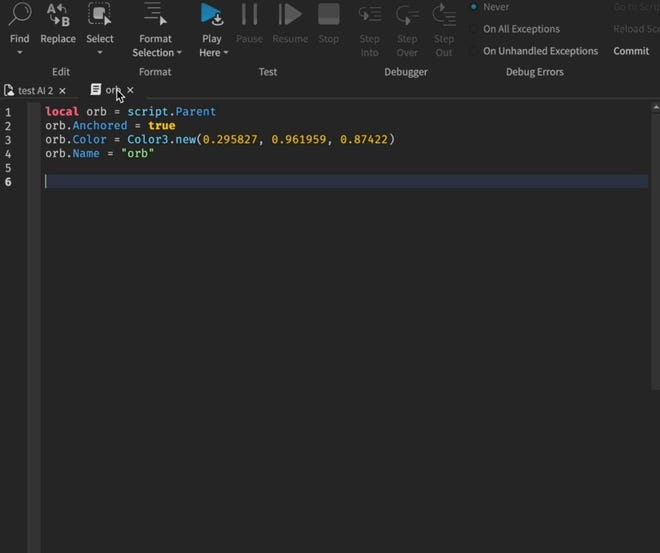

One of those demos was from Roblox Studio, the platform on which Roblox’s aspiring young creators build their games. Roblox already had a few AI-powered tools in the wild: a thing called Code Assist, that “suggests lines or functions of code as creators type”, and automatic chat translation, a real the-future-is-now feature that translates in-game messages between players in real time as they’re sent. Roblox says its creators have adopted about 300m characters of code from Code Assist, and translated an astonishing 19.7bn messages in the 30 days since the chat feature launched.

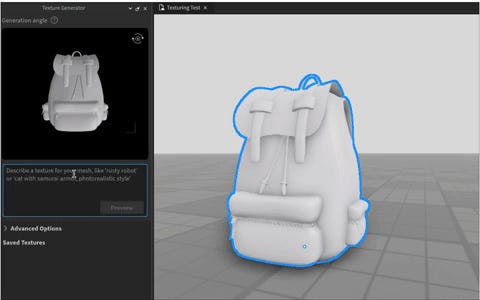

The latest demos, however, shown to me by head of Roblox Studio Stefano Corazza, felt the most directly related to what Roblox is all about: helping amateur developers create things easily and rapidly from scratch. The first was called Texture Generator, and began with a blank, white-grey backpack object on Corazza’s laptop.

“This is our demo scene studio, here’s a backpack that I just downloaded from the internet. And then you go crazy with the style,” Corazza said.

“Oh! You mean me come up with something?” I replied. “Please! Because otherwise it feels like it’s rigged, right?” Corazza laughed. “Er, okay, how about a camouflage style backpack with… gold buckles” is the best I could come up with – I can feel Derek Guy preparing the quote tweet already – but Corazza dutifully types in “camouflage style backpack with gold buckles” and, voila. In a few seconds, the textureless video game object is now a fully textured and truly hideous backpack made of green-and-brown camouflage material, with sparkly gold buckles. To save it and have it functioning and appearing in the game, it takes about 30 seconds more.

This also works for anything in the world around our current placeholder avatar. Corazza picks out a tile on the floor that currently looks a bit like a square wooden hatch, and with a few keystrokes turns it into one made of steel, picking out the exact steel texture from a range of options the software throws up – checker plate, polished, etc. After that, a few more lines of plain English and he’s added a mechanism that makes the now-steel tile raise upwards when touched by the player, as you might want it to for a platforming game (the tile clips through the character in this instance, and then the two get sort of awkwardly fused together because a few more lines of stipulation are needed here, but you get the idea. “That’s a different problem,” Corazza laughs.)

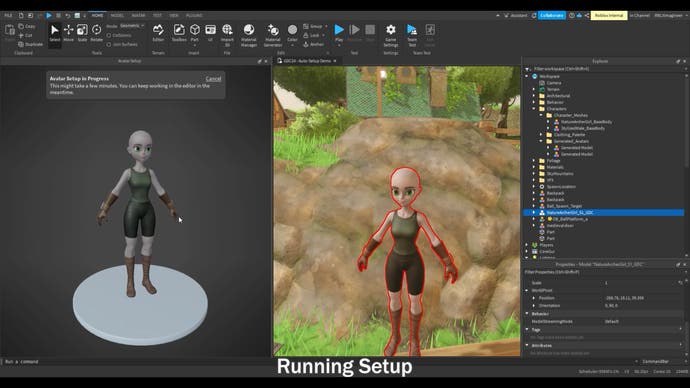

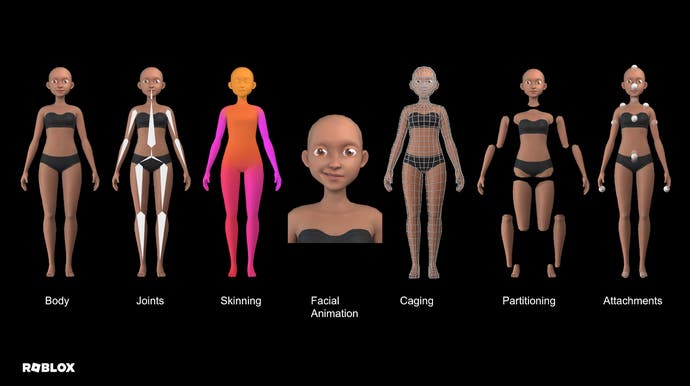

The second demo was for something similar, called Avatar Auto Setup. In this one, a static 3D body mesh can be rigged, caged, segmented, and skinned (that’s being given a skin, not having its skin removed, for those new to development terminology), and like before all of this is done in sections and off the back of just a couple of plain language phrases entered into the system.

“Basically, we apply the skeleton to the body, we figure out where the joints should be, and then we apply all the facial shapes to the character that it can do. We also do caging, so that I can equip it with any piece of clothing, and so basically, the avatar becomes fully functional,” Corazza explains. Altogether it takes about two minutes. I asked Corazza if it’s as broad as me being able to type “make me a werewolf” into the text prompt and that being possible. “You are reading into our roadmap,” he laughed.

“What you described is what we call photo-to-avatar. It’s something we have seen, we have shown at RDC [Roblox Developer’s Conference], some early concepts and something we are working on. I don’t think we have communicated a timeline, but as you can imagine that’s pretty high up on the priority list.”

Coming back to the impact of the Avatar Auto Setup feature, “I was the founder of Mixamo in 2008,” Corazza said, “that was a long time ago. We rolled out the first auto-rigger for the body, and then we tried to tackle the head of the rigging, and we realised how hard that problem is. So this was many engineering years in the making, but now we feel it’s going to be a game changer.” Even when using chat, Corazza explains, the character’s facial movements and lip syncing will all work alongside it as you’d expect.

The back-to-reality moment here is looming, however, and comes in the form of all the usual questions around generative AI. How does Roblox handle licensing issues for those AI generated textures, for instance – and what data is its generative AI trained on?

“So there’s no difference [between] whether I took this texture from somewhere else, or I made it with AI, or I made it with Photoshop by hand, right?” Corazza said. “Everything is treated in the same exact way. If you create it with AI, or you make it yourself, you own the IP. If it’s someone else’s 3D model, and you’re infringing, and you’re pushing that in the game, then someone can find out and then report it – and when they report it then we can take action.”

As for the training data, a statement in an FAQ on the Roblox site states “The Texture Generator is trained using third-party and in-house models on publicly available data and does not use any Roblox creator data.”

“We partner and we also have our internal models,” Corazza explained, without specifying further. “And so in this specific process it is a mixture of those, where there’s some external open source models that we’re using, and also internal ones that we train, and so it’s a combination.” Models can be tweaked numerous times, meanwhile. “It’s really like building a racing car, where you swap out the engine every lap.”

The next worry again is safeguarding, which has long been a concern for Roblox given its vast popularity with children. Corazza explained that much of this is actually handled by AI as well, moderating both the prompts before anything is generated and also what’s created from them after the fact, although he didn’t fully specify how that post-generation moderation worked.

“It’s a great question – we believe that UGC really explodes for the players when they actually have full control,” he said. “So there’s a big difference between, say, ‘here are like 10 different colours that you can pick for this thing,’ versus like, you go wild and you type the text, right?”

“But at the same time, the boundaries are a lot wider. And so we do pre-moderation on the prompt, before that is sent to our back end, and then we do post-moderation on what comes out. Safety is our number one product, as a gaming platform, and so we want to make sure that whatever comes out is legit and, you know, good content, non-offensive, non-toxic and everything. So there’s a lot of AI on the back end, to make sure that the assets are okay, the experience is okay. The most difficult thing that we do, I think, is real time chat moderation. We have a whole division that is dedicated basically to that.”

The usual caveats of AI aside, in actual practice this all looks about how you’d expect for Roblox: various art styles and texture qualities mashed together, slightly shonky animations and in this case, a migraine of colour and angles swirling around in the loosely fantasy-themed fairground backdrop for good measure. But equally in practice, this doesn’t really matter. Roblox isn’t popular for its artistic splendour or visual fidelity, as Corazza points out.

“I’m sure there’s a lot of tension around the quality, right? Like the look – and of course we don’t have like a triple-A level of fidelity, but we have to run this thing on a, you know, 10-year-old Android phone,” he said. “So we have done A/B tests and what we found is that performance on low end [hardware] is more important for a game developer than the quality.”

Corazza gave an example: “Playing with 10 of my other my friends in a game, and then this one guy, that for him it’s running at five frames-per-second because he’s on an older Android phone, he’s gonna be like, ‘Hey, this is not working for me, let’s switch over,’ and then all 10 will leave and go to another game that may have lower fidelity and visual quality, but at least everybody can play a 30 frames per second.” Similarly plenty of Roblox developers have done A/B tests of their own, Corazza explained, where they “lowered the quality, increased the FPS, and it was more successful. Sometimes people forget that, you know, our stuff is not designed to run on like the highest Nvidia GeForce – 75 percent of our players are mobile.”

As the industry has hit its recent walls, the topic of growth has also become a growing concern, with this notion of being playable on the lowest possible hardware specs understandably gaining traction. “It’s an expanded view of what gaming means,” as Corazza puts it, “also gaming as a social experience, as opposed to the classic, single-player first-person shooter triple-A thing, which is just one category – it’s not the full ecosystem.”

“I don’t think there’s an either-or,” he added. “I think that we are in a super multifaceted ecosystem, and there’s all this space for every genre, every type of game and every dev. Roblox is also like – the variation is humongous.”

Between generative AI and user-generated content, or UGC as it’s become known in development terms, Roblox Studio is effectively straddling a pair of buzzwords that have become hugely popular. To some, one or the other is an industry panacea, a way to fix productivity woes on the industry’s supply side, or explode outwards to reach new audiences for greater demand. Corazza wasn’t going that far, naturally, but he was also optimistic as you’d expect.

“I think one is helping the other,” he said. “So we’re delivering in UGC, and then with AI now, all this AI goodness is in Roblox Studio – but our goal is to bring it in Experience,” the playable things created by Roblox’s community. “As the cost goes down, as the time to compute is faster, we can put it in front of our consumers at 30 seconds wait, for creators this is like ‘Oh my god, this is saving me two days of work.'”

As for UGC, “I see how rewarding it is for players, the shift from passive players to creators,” Corazza said, describing it as like the change between “watching a movie, versus making a movie with your friends – it’s a completely different experience.” The industry is “seeing a big shift from players to creators, and AI and UGC are basically enabling that,” he said. “So, given we are a true UGC platform, we can only be optimistic about it. It’s a world where the players are more empowered, and they’re having more fun, and they do it together with their friends in a nice and social way.”

Corazza also spoke to Eurogamer about the ongoing notion of child exploitation in Roblox, claiming the kids themselves don’t see it as exploitation, but as “the biggest gift”.

[ad_2]

Source link